In a now-viral trailer for the upcoming Barbie movie, Margot Robbie’s Barbie silences a dancing crowd with her query: “Do you guys ever think about dying?”

In this post, I would like to— and this is a first for me— pick up where Barbie left off.

Perhaps it’s a natural part of aging, or perhaps it’s because our species feels imperiled for this or this or this reason, but I find myself contemplating death with more frequency and gravity than ever before. A handful of psychedelic experiences gifted me a form of death-rehearsal, during which I became acquainted with death’s tremendous and terrifying beauty. As a result, I wrote this poem, and this poem, and this poem, and this poem.

(Spoiler Alert: I guess all of my poems are about death?)

In July 2021, I found myself at the sites of two separate “active shooter” scares in Las Vegas and New York. Both were false alarms, yet both caused large-scale panic and hysteria: including many large men pushing me down in their race to scale the nearby fences first, and another man denying me sanctuary in his car during the stampede. That first evening, I— a privileged person with the luxury of feeling generally safe in the world— experienced what most humans are forced to come to terms with early in life. My death might not be accompanied by feelings of goodwill; in fact, my life might conclude with feelings of horror and disappointment in my fellow beings.

Would such a death alter the essence of the life lived before it? In other words: what, if anything, does death have to do with life?

In response, here are my recent musings on death; furnished by a constellation of thinkers I admire.

When it comes to the big questions, I like to start with nature. In the natural world, nothing is wasted. All Death is Compost, and Compost is Life, Renewed. Compost is the courage of fresh life commingled with the wisdom— the nourishment— of death.

By observing plants and animals, we conclude that their ever-present relationship with death enables a present-tense relationship with life. Senses are heightened, attention is sharpened, and any sense of existential angst diminished. Humans are the only species for whom (as far as we know) death is a source of neuroses rather than—strange to say it— motivation.

But some humans are harnessing the concept of death as a tool for reflection, revitalization, and reverence. In an interview on Sam Harris’s Making Sense podcast, longtime meditator, esteemed physician, and pioneer of the psychedelic renaissance Roland Griffiths describes his terminal cancer diagnosis as augmenting his “sense of joy and wonder.”

Griffiths’s interview is truly breathtaking: as in, its tender contemplation of death robs the listener temporarily of breath. For isn’t that what all great art aspires to do: shock our systems with a burst of life, with a tiny death? Art is the delirious plummet of free-fall, darting through the embrace of those two foxtrot partners, Life and Death.

My dear friend Chloe— whose purity of spirit and gift for contemplation astound me—writes a remarkable Substack called Death & Birds. In a major plot twist, it is a Substack about death, and also birds. Chloe is on a mission to revolutionize our relationship with death: how we approach, discuss, and ultimately greet it. In this poignant post, she suggests (convincingly) that our cultural phobia around death places undue emphasis on youth, beauty, productivity, and industry. Drink at this wise woman’s well and you will emerge a kinder, truer being.

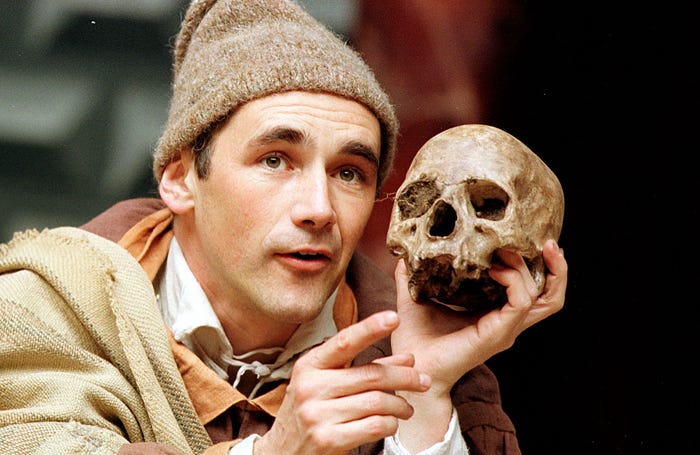

And of course, no danse macabre would be complete without a trip to the theatre. In two recent plays, the presence of death provides opportunity for clarity and insight.

The first is James Ijames’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Hamlet adaptation, Fat Ham. This contemporary retelling stages Shakespeare’s tragedy without Shakespeare’s language: in it, Hamlet figure “Juicy” reckons with his father’s death and his mother’s recent marriage to his uncle. Ijames recasts the royal family as a modern Black family running a barbeque business. This clever update activates Shakespeare’s motifs of death and decay: something is indeed “rotten in the state of Denmark,” as Fat Ham literalizes the Shakespearean imagery of “maggots,” “sullied flesh,” and “rank” offense.

(In Shakespeare’s text, Hamlet complains that after his father’s death, his mother’s wedding was so hasty that “the funeral baked meats / did coldly furnish forth the marriage tables.” Leftovers, amirite?!)

Fat Ham’s barbeque business is an emblem of violence and rot: a legacy of patriarchal harm presided over by Juicy’s father and uncle. Yet it is also an opportunity for nourishment, communion, and pleasure, as the family moans in ecstasy over a shared meal. This duality begs the question: is there a world in which death nourishes us?

(Cue: an animal-rights post for another time.)

More importantly, Fat Ham uses Hamlet to critique patriarchal endorsement of violence and death. As a character, Hamlet is famously preoccupied by death, yet here Juicy wavers in killing himself and others because his father-figures are agents, as well as victims, of death. Both Juicy’s father and his uncle urge “manly” harm over softness. Fat Ham asks, in a number of ingenious ways: “what would life be like if we chose pleasure over harm?”

Tellingly, both Juicy and the play itself refuse to dispense death in the way its “manly” characters do. Instead of being murdered by Hamlet (as he is in Shakespeare’s text), the Claudius villain-uncle character dies of what might be called “toxic masculinity.” Choking on a piece of meat, he refuses care and shrinks from Juicy’s touch (Chloe’s earlier point about death and our need to feel invincible comes to mind). Similarly, Fat Ham subverts audience expectations by denying us the bloodbath of Shakespeare’s tragedy (nine out of Hamlet’s eleven central characters die). When that final bloody scene arrives, Juicy and his family members simply gaze at the audience and ask: “Do you mind if we just… carry on?”

The characters proceed to clean up the (literal and figurative) mess of the barbeque, before ending the show on a note that is so joyous and so wholly unexpected that I dare not spoil it for you (“rotten” pun intended). Fat Ham’s irreverent, euphoric ending is a challenge to canonical narratives: both the violence of Shakespeare’s text, and the brutality of a society in which Black citizens— real and fictional— are being murdered with impunity. This play’s decision to circumvent needless death, and to replace the anticipated gloom of death with a scene of catharsis and jubilation, helped me consider death differently. Heeding Fat Ham’s parting message, we might ask: what are the kinds of endings that we wish to write for ourselves?

The second play is Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’s high-school reunion drama, The Comeuppance. I am an obsessive Jacobs-Jenkins stan, and therefore ran to see this new work at the Signature Theatre. The Comeuppance is a metatheatrical masterpiece in which the dashed hopes, deflated fanfare, self-aggrandizement, and yes, even the comic and erotic valences of a high school reunion coincide with that Grand Reunion awaiting us all.

In this production, Death is a character who takes turns occupying the bodies of various actors, in order to address the audience. Like theatrical spectators, Death is a voyeur who observes the theatre of our lives. The Comeuppance illustrates how an individual’s relationship with death is a lifelong partnership, rather than a brief acquaintanceship at the moment of death. In this play, Death explains its longstanding connection to each character: this person is a war veteran, that person is a doctor, this person experiences suicidal ideation, that person had several miscarriages, this person lost a parent at an early age. In a tone more suave than sinister, Death argues that its intermittent presence can imbue our lives with greater meaning.

What I appreciated most about The Comeuppance was its deft handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. With the electrifying exception of Bo Burnham, I have yet to see any artist tackle COVID well; modern audiences often seek entertainment to escape thoughts of the pandemic.

Yet in The Comeuppance, Death reminds us that in recent years “you thought about me… a lot.” In a line so plaintive that it, too, robbed me of breath, Death observed: “how you were during that time— kinder, more present— made it easier to root for you.” The play ends with an evocative aural art piece (a-piece-within-a-play) that reveals how Death is accompanying us always, even as we shut our ears to its siren call.

From Barbie to Shakespeare, from meditation to meat… all of these perspectives suggest that Death is a wonderfully strange companion. The plays, podcasts, and pieces described here imply that death is an essential part of life; one that (when activated healthily) brings more life to life.

As I waded deeper into my exploration of death— and acknowledged my own prior avoidance of it— I was shocked to realize that death is everywhere: in all the poetry I love, in all the nature I cherish, in all the songs I play. Digesting this revelation, I felt as though I’d been welcomed into the ranks of artists and philosophers who have been preoccupied by death for centuries.

(Revised Spoiler Alert: I guess all poems are about death?)

… or as A.E. Stallings puts it much more poetically…

One day you realize it. It doesn’t need to be said—

Just as you turn the page—the end—and close the cover—

All, all of the stories are about going to bed:

Goldilocks snug upstairs, the toothy wolf instead

Of grandmother tucked in the quilts, crooning closer, closer—

One day you realize it. It hardly needs to be said:

The snow-pale princess sleeps—the pillow under her head

Of rose petals or crystal—and dreams of a lost lover—

All, all of the stories are about going to bed;

Even the one about witches and ovens and gingerbread

In the dark heart of Europe—can children save each other?—

You start to doubt it a little. It doesn’t need to be said,

But I’ll say it, because it’s embedded in everything I’ve read,

The tales that start with once and end with ever after,

All, all of the stories are about going to bed,

About coming to terms with the night, alleviating the dread

Of laying the body down, of lying under a cover.

That’s why our children resist it so. That’s why it mustn’t be said:

All, all of the stories are about going to bed.

I’m willing to wager that all of our finest art has a tinge of Death about it. Revisit a piece of beauty that moved you deeply— I promise, death is in there somewhere. It’s as if Death winks at the artist and murmurs: “I’m here, but I’ll give you a head start. Show me what you’ve got.”

Art and Death each amplify Life. Art is Life with Death on its heels.

While writing this piece, I asked a handful of loved ones: “What do you think happens when you die?” All of them, without exception, described the beautiful humility of the unknown. For me, this is Death’s most poetic and audacious quality: it seeks to wed us all, yet gives nothing away.

This glorious, love-studded, complicated life— the one in which we try and fail to remember that nothing is within our control— ends in a Great Mystery. Life’s curtain closes with equality, for no one has the answers nor ever will.

What a delight! What a feat of benevolence and inclusivity! What a true piece of performance art: to spend our lives walking towards the same fate, the same riddle!

Dear ones, let me tell you… for we may not have another opportunity… it is an honor to approach the unknown with you.

I’ve loved reading your comments on previous posts. If you’d like to share, I’m eager to hear: what is your relationship with death?

(If you enjoy my writing, go wild and click the ❤️ or 🔄 button on this post so more people can discover it on Substack!)

Sweetest love, what a gift to hear your musings on my most beloved topic, and what an honour to be considered a thinker you admire! I blush at the thought 🥰

You speak to so much forgotten wisdom; Death is supposed to be nourishing, all Death. I highly recommend watching Caitlin Doughty visiting the Human Composting Facility, where it’s possible for you to literally be given earth made from your beloveds (https://mrtroyford.substack.com/p/notes-from-the-alley-4)

We are exclusively neurotic—there’s a whole evolutionary psychology theory called ‘Terror Management Theory’, and it pretty much presupposes that literally everything that humans do, create, believe in—everything—it’s all just creative ways to stop ourselves from thinking about Death. Personally, I think they go a little overboard, I don’t think that all art & all religion is about avoiding mortality salience; but it’s interesting that such a school of thought that exists…

Death illuminates and clarifies. Stephen Jenkinson (my mentor, unknown) tells a profound story in Die Wise, where he gets a call from a hospice nurse who’s been given a terminal diagnosis. He’s the ultimate Death-guide, so they talk a little, and he suggests she take a few days to let the news settle and then call him again. She calls him back a few days later and, low & behold, the doctors had given her the wrong results. She was going to be fine. They sat in silence for a minute and he asked her how she was feeling—she just let out a primal wail, she was keening, and not with relief. Once settled she explained that for just a few days, everything was crystallised, she saw everything for what it truly was for the first time. Everything was miraculous. And she felt as though, with the correction of her diagnosis, that that had been stolen from her…

I would love to see Fat Ham, it sounds incredible. Did you ever see The Cook, The Thief, His Wife & Her Lover? Your description of Fat Ham brought it to mind…

Thank you again for your exceptionally kind words, my love. Oh and your poetry! Thank you, thank you for your poetry…

When I worked as a hospice volunteer, I remembered and found that the words of Ram Das were true: "When you are in the presence of someone near death, you are in the presence of Truth." Of course, we all are nearer to death than we like to think, and in the presence of Truth, if only we could see it. Thanks for shining your light in this place that is not as dark as we are led to believe.