A tiny revolution is unfolding on 44th Street between 7th and 8th Avenues. On this block, you’ll see three marquees featuring seasoned actresses in legendary roles: Laura Donnelly as Veronica in The Hills of California, Nicole Scherzinger as Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard, and— all hail the queen— Audra McDonald as Rose in Gypsy.

Let me tell you why I’m currently swooning over this constellation of shows. As I’ve written before, I love when women— both the performers and the characters they inhabit— get to be fierce and imperfect and complicated onstage. In The Hills of California, Sunset Boulevard, and Gypsy, all three performers are middle aged women playing ambitious, tyrannical, fame-obsessed characters. Donnelly’s Veronica and McDonald’s Rose are single mothers determined to achieve security and significance for their daughters at all costs, whereas Scherzinger’s Norma is an aging film star clinging to her former glory. All three productions involve exploitation, moral complicity, and unremitting quests for stardom. These plays, and the women in them, are not pretty. Instead, they are ruthless and uncomfortable.

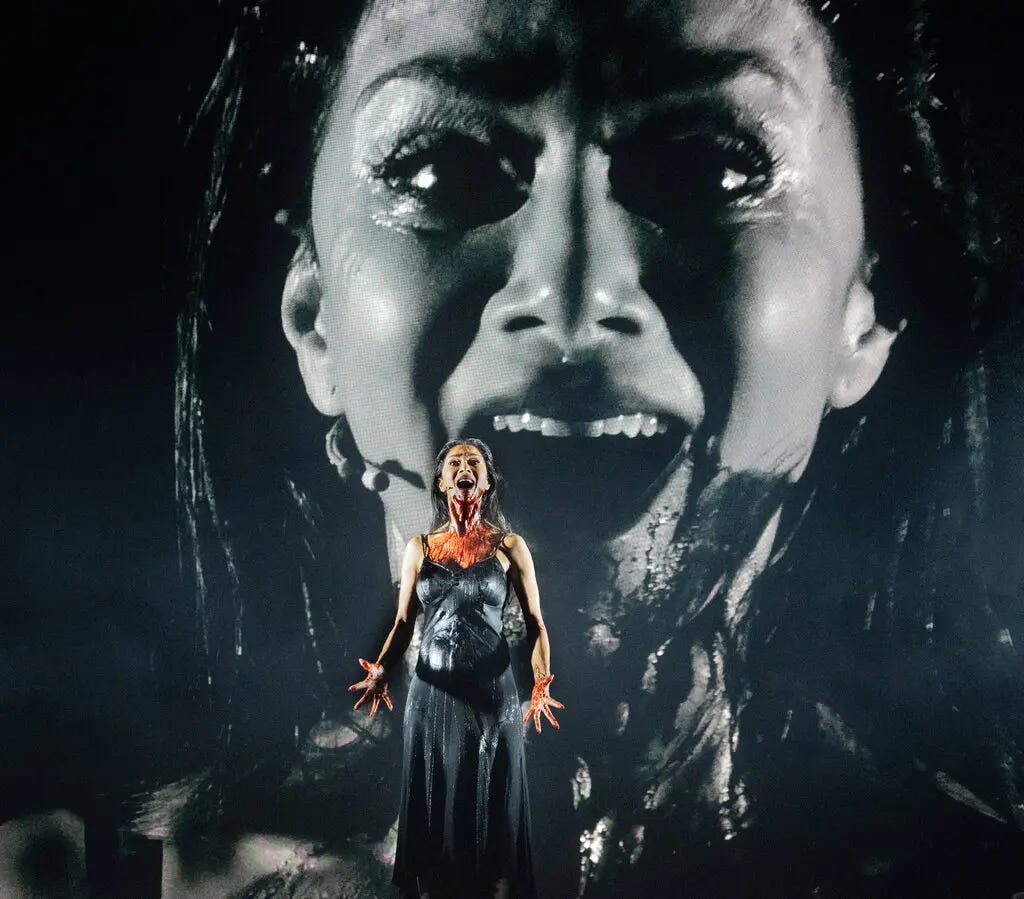

How does one possibly contain such untamed ferocity? In these productions, each director enshrines his leading lady differently. If you’re Sam Mendes directing The Hills of California, you follow the classic recipe for a Jez Butterworth play and oversee a massive, hyper-realistic set design (in this case, a seaside motel). If you’re George C. Wolfe directing Gypsy, you construct a visual banquet of a classic stage musical, complete with flyaway set pieces. If you’re Jamie Lloyd directing Sunset Boulevard, you stick to the Jame Lloyd aesthetic signature: stark lighting, minimal set, and a plethora of cameras for live-action sequences.

These design choices are crucial in reinforcing how all three plays interrogate “performance” as a concept. Gypsy’s proscenium arch with its bright Broadway lights may as well be the metaphorical frame Rose uses to perceive the world— showbiz and stardom are the beginning and end of her sightline. By integrating live cameras and the literal streets of Broadway, Sunset Boulevard draws parallels between a camera-hungry Hollywood and Broadway’s theater industry. The Hills of California’s set is dominated by staircases, which signals the play’s fixation with ascension and descent: in terms of fame, as well as mortality and morality.

But in all three productions, the best visual moments are when the women are left alone: Scherzinger’s Norma surrounded by mist and belting her heart out, McDonald’s Rose in the footlights with tears glistening on her cheeks, Donnelly’s Veronica downstage shutting her eyes against the abuse she hears upstairs. When situated in relative emptiness, these performers strike up direct relationships with the audience: relationships taut with hunger, need, gratitude, and triumph. Scherzinger’s Norma and McDonald’s Rose sing straight to the rows of spectators, enlisting and acknowledging them as loyal fans (“As If We Never Said Goodbye,” “Rose’s Turn”). In these sequences, multiple performances are placed atop each other for dramatic effect: the dynamics between these characters and their imaginary audiences fuse with the dynamics between these famous performers and their theatrical audiences. Art imitates life and life imitates art, baby!

In my PhD dissertation, I explored how specific performing bodies, with their attendant performance histories, can enhance the (meta)theatrics of a stage production. For instance, Nicole Scherzinger’s pop-diva history as the lead singer of the Pussy Cat Dolls is legible in the Sunset Boulevard’s contemporary choreography and use of television screens. Laura Donnelly is the partner of The Hills of California playwright Jez Butterworth, and is well-known to most Broadway spectators as the leading lady in two of his previous plays: The River and The Ferryman. Audra McDonald is a Broadway legend, particularly in the realm of musical theater. These three women have considerable performance histories that lend layers of metatheatrical texture to The Hills of California, Sunset Boulevard, and Gypsy: each one a performance about performance.

These productions harness specific performing bodies to accentuate their themes. In The Hills of California and Gypsy, the presence of actual child actors onstage amplifies each play’s themes of child abuse and exploitation. In The Hills of California, Donnelly plays both Veronica and her daughter Joan, to underscore the karmic ties between these two characters. By casting Black performers in Gypsy’s leading roles, the show creates rich layers of commentary about performance histories: including transforming Gypsy Rose Lee’s strip acts into a visual and choreographic nod to the iconic Josephine Baker.

I could ramble on and on about the ways in which these productions swell to meet the immensity of their stars. But instead, I’ll leave you with my lasting impression after seeing these shows. All three productions answer the challenges contained within them— by creating rich, dynamic, commanding roles for middle-aged women. Enterprising characters like Norma, Veronica, and Rose are grasping for power and relevance by any means necessary; determined to match the viciousness of the showbiz worlds they inhabit. But performers like Donnelly, McDonald, and Scherzinger do not need to beg for scraps: these are roles on which they can feast. No more feuding to stay current. No more sexual extinction after the age of thirty. No more ingénue imprisonment. Friends, I’m delighted to report that we are entering our Middle-Aged Harpy Era.

Already Mr. Demille, I’m ready for my closeup. Mama’s goin’ strong. Mama doesn’t care. Here she is, boys! Here she is, world!

If you enjoy my writing, go wild and click the ❤️ or 🔄 button on this post so more people can discover it on Substack.

Read my other theater reviews here, here, here, and here. Read my other pieces on feminist expression here, here, and here.

This piece is dedicated to my mother, who first introduced me to theater, and who continues to teach me how to be a strong, complicated, independent woman.