Hide and Seek

the path of highest beauty

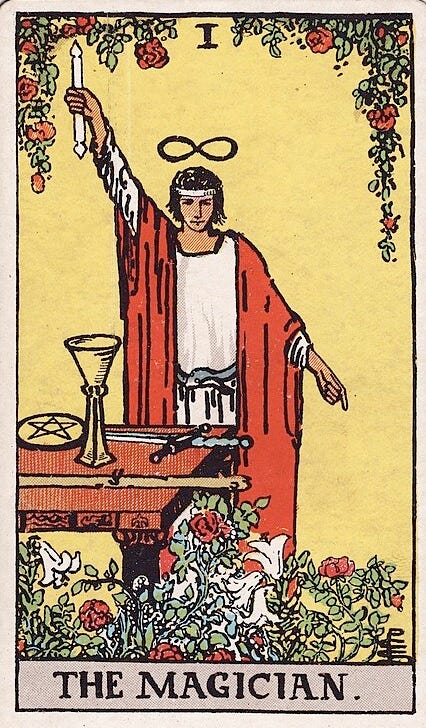

Last fall, I visited the Whitney Museum of Art with my magical and mischievous friend Mark Clearview. Mark is a magician by trade. As we strolled through the exhibits, I displayed a gallant five minutes of restraint before launching my all-out offensive: would he reveal his magician’s secrets about how he accomplished his tricks?

Mark smiled down at me; half-amused, half-pitying. After all, this was probably the first time anyone had exercised the ingenuity, originality, and daring to ask him such a groundbreaking question. He replied: “In cases where the method for achieving the trick is more beautiful than the trick itself, then yes, of course I would share it with you.”

I stood stunned, having received what felt like an off-hand explanation of God and the Known Universe. Since that afternoon, Mark’s comment has surfaced in my brain with astonishing frequency. Because I trust what lingers, I’d like to hold this concept up to the light and admire its refractive splendor. When seeking the path of highest beauty, when do we wish to have our way illuminated with knowledge, and when do we wish to remain entranced by mystery?

IN FAVOR OF METHOD

I’ve spent years of my life practicing literary criticism and analysis: essentially, the method of interpreting and explaining a piece of art in order to make its experience richer. In short, I’m a method gal, through and through. The more I understand the context and mechanisms behind a work of art, the deeper my appreciation of it.

For instance, last night I read a poem by Edward Thomas that moved me to tears. My first reaction was merely to absorb the exquisite, haunting ache of his lines. Then I returned to the poem to study it in greater detail. The technical elements of the poem— its rhyme scheme, its striking use of enjambment between the seventh and eighth lines, its embedded reference to Shakespeare’s Love’s Labour’s Lost, its employment of double meanings (“salted,” “inn,” “poor”)— augmented my appreciation of the piece. Then I situated the poem in its historical context: Thomas wrote it right before he voluntarily enlisted in World War I, consumed by guilt that others were fighting while he was not. He died in the Battle of Arras a year later. I didn’t need this context to understand the poem, but I can’t deny that the knowledge created a more poignant, layered reading experience for me.

I’m always hungry for an illuminating explanation. When I understand more about trees, or the Giant Pacific Octopus, or the number zero, I feel that my awe for life only increases. I want the words “We Learned” etched on my body or my tombstone, for I believe this is what we’re here on earth to do. Spill those magician’s secrets, baby!

If we honor the wisdom of Explaining the Method, how might we explore the world and share ourselves? Can we explain ourselves in ways that might amplify our essential, mysterious beauty? When we reveal our contexts, our complex mechanisms, our hidden desires and dreams, perhaps we offer the world a chance to appreciate us in greater detail.

IN FAVOR OF TRICK

On the other (sleight of) hand, I believe in the beauty of the unknown. I’ve advocated for the oblique in the contexts of science, divorce, art, and death. To make peace with mystery is perhaps the most noble and humbling human endeavor.

David Whyte describes the act of hiding as “one of the brilliant and virtuoso practices of almost every part of the natural world: the protective quiet of an icy northern landscape, the held bud of a future summer rose, the snow bound internal pulse of the hibernating bear.” Whyte believes that “what is real is almost always to begin with, hidden, and does not want to be understood by the part of our mind that mistakenly thinks it knows what is happening. What is precious inside us does not care to be known by the mind in ways that diminish its presence.” In this way, “hiding leaves life to itself, to become more of itself. Hiding is the radical independence necessary for our emergence into the light of a proper human future.” What great beauty might hiding afford? How can we fall back into the vastness of quiet, unknowable glory?

The two Great Pillars of Existence— Life and Death (or: God and Death)— refuse to be known entirely. We strive to acquire knowledge of their methods; piecing together what we know of molecules and compost and gravity and ritual as we attempt to cobble together some kind of coherent formula. But I contend that fully knowing Life or Death would diminish our experience of their beauty. We were built to seek, to fumble in the sly withholding darkness, to writhe in the blessed dirt, to dare our imaginations to their most intrepid, unreasonable heights.

One of my favorite aspects of life is that it ends in mystery… for all of us. No one— but no one— knows what happens after we leave our bodies. Mere decomposition? An ascent or descent? A perpetual return? A dissolution into everything? Anyone who purports to know What Comes After (to quote the timeless film The Princess Bride) “is selling something”. Death is the Great Mystery, the Great Equalizer. We are all headed towards one last, breathtaking magic trick. How we travel there— our method of living— is the beauty that precedes it. Let us be dazzled, then, by all we know and shall never know, before the curtain closes.

If you enjoy my writing, go wild and click the ❤️ or 🔄 button on this post so more people can discover it on Substack. Thank you Mark Clearview for your endless enchantment; I like questing for answers— and running from them— with you.

Such a great piece to reflect upon and start the week with.

beautiful!