In short: I am not entertained.

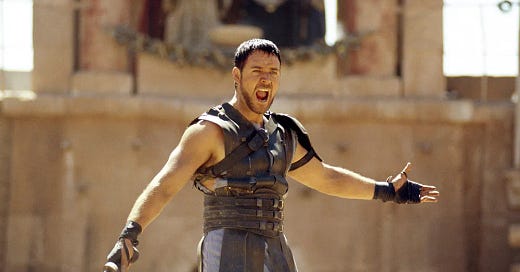

Let’s begin with a journey into cinematic history. Gladiator is one of my favorite films of all time (second only to the masterpiece that is Pixar’s Ratatouille, which I’ve praised here and here). Ridley Scott’s epic tale of “the general who became a slave… the slave who became a gladiator… the gladiator who defied an empire” is riveting, action-packed, and well acted. Moreover, I credit Gladiator’s star— an armor-clad Russell Crowe— as the catalyst of my adolescent sexual awakening. Saddle my horse and take me to ancient Rome, honey!

Despite its gory content, Gladiator’s underlying message is surprisingly pacifist. Crowe’s Maximus is a military commander who is duty-bound to serve Rome, but longs to return to his farm, wife, and son. When Maximus defies the scheming Emperor Commodus (Joaquin Phoenix), Commodus orders Maximus’s execution— and kills his family for good measure (classic villain behavior). Maximus evades death and is sold into slavery as a gladiator, but initially refuses to fight even when attacked. Only when he enters the arena does Maximus fight— not because he fears death, but because he wishes to meet his death as a warrior. In fact, Maximus’s most famous line— “Are you not entertained?”— is a politically provocative barb hurled at the spectators who gather in the arena to revel in bloodshed.

One of my favorite scenes in Gladiator is when Maximus exits the arena as the crowd chants his name. In this moment of supposed victory, Crowe’s face exhibits only grim resignation and detachment. Maximus is a man who prays to his ancestors, loves his faithful dog, and touches foreheads with his friend as a gesture of intimate homosocial affection. In fact, Maximus earns the appellation “Maximus the Merciful” when he refuses to kill his rival Tigris. According to Tales of the Scribes, writer William Nicholson was hired to revise Gladiator’s script to make Maximus a more sensitive figure, because the film’s creative team “did not want to see a film about a man who wanted to kill somebody.”

Maximus isn’t the sole pacifist vehicle in Gladiator. In the film, we learn that the esteemed Marcus Aurelius (Richard Harris) closed down the arenas during his reign as emperor. It is his son, the wicked Commodus, who commissions the gladiatorial games as a political weapon. Commodus uses these games to distract the Roman public with spectacle while he quietly erodes the pillars of democracy by dismantling the senate. (Sound familiar?) Throughout the film, director Ridley Scott details the horrors of the arena: we see an enslaved gladiator crying and urinating in fear as he awaits his certain death by combat.

Why am I dragging you back through the plot of an action film from the year 2000, you ask? Because as I sat through Gladiator II (2024) this past weekend, I felt like Maximus: tired of bloodshed and longing to return home.

I won’t bore you with the plot of Gladiator II, which somehow manages to be both a rip-off of the original Gladiator and riddled with a number of new bewildering plot holes. Despite the presence of catapults, swords, arrows, and— I kid you not— CGI baboons, eyeshadow was by far the most violent weapon in the film. The acting was tepid throughout, save for the sparks flying between Paul Mescal’s Lucius and Alexander Karim’s Ravi, which— I give you my word— will incite me to petition Paramount Pictures for the homoerotic spinoff we all deserve.

Gladiator II makes a number of half-hearted pacifist gestures, yet even its purportedly peaceful ending feels lackluster. Two warring armies decide (with half the population missing, mind you— better luck next time, ladies!) to lay down their arms to make room for… the Roman senators? Those craven men who, only twenty minutes earlier, were willing to let a literal monkey run the Roman empire because a crazy dictator with syphilis said so? (Sound familiar?) Gladiator II is a mere echo of its predecessor: parroting lines about revolutionizing the Roman republic, yet glorying in Roman violence throughout.

Perhaps it is my own age, as well as my perception of this era’s political brutality, that determined my distaste for Gladiator II. Rest in peace, ye adolescent brain: content to merely drool over Russell Crowe’s biceps! Welcome, old crone brain: eager to destroy a bucket of popcorn and a blockbuster plotline with equal relish! With twenty years between my Gladiator viewing experiences, much has changed within and without. During Gladiator II’s opening scene, in which Romans lay siege to a Numidian province, I felt like the Capitol elite in The Hunger Games: watching violence for entertainment as actual war ravages innocent civilians in Gaza. By contrast, I found myself energized by a different Hunger Games-like sequence later in the film: a fleeting moment of promise when Lucius (Mescal) and Acacias (Pedro Pascal) thwart the oppressive Roman regime by electing not to kill one another in the arena. Now we’re talkin’!

The word sequel, which stems from the Old French sequelle and the Late Latin sequela, means “a consequence of an event or action, a corollary.”

Gladiator ended with a defeated emperor and a promise to revitalize the Roman republic. Gladiator II began with a rinse, repeat— only to end with another defeated emperor and another promise to revitalize the Roman republic. What about the consequences? What about the challenges of designing public policy and uniting a fractured nation?

In America, Hollywood invests in sequels because they are good financial bets with established IP. I believe our capitalist system needs a change: because when we’re motivated by profit, we end up telling the same stories over and over again. I want Art that takes risks. As much as I loved Gladiator, we don’t need to Make Rome Great Again.

So… let’s talk about sequels. In other words, let’s talk about consequences.

Gladiator is a paean to Western individualism and exceptionalism, which is why many of us find it thrilling. Culturally, we’re primed to root for That One Hero who defies all odds. In fact, my dad (Tom Gilovich) and Jesse Walker co-authored a paper on “the streaking star effect,” which details “people’s greater desire to see runs of successful performance by individuals continue more than identical runs of success by groups”. The streaking star effect explains why many of us may love rooting for a single exceptional victor again and again, like Roger Federer (or even for Michael Jordan in that Gladiator-esque documentary series, The Last Dance), even as we feel irked by the longstanding reign of a team like the New England Patriots.

But personally? Twenty years, countless global crises, and several holy-moly-guacamole psychedelic trips later, I’m no longer a worshipper in the Cult of the Individual. Instead, I want to see what happens in community. I want to see sequels that uphold the collective as a source of power, strength, and innovation. Working together— loving each other— seeing each other— is harder than any of us might have believed possible.

Nowadays, I’m downright bloodthirsty for new ideas. I crave new stories, or old stories told in new ways (see: James Ijames’s Fat Ham, Jackie Sibblies Drury’s Fairview, Branden Jacobs Jenkins’s An Octoroon). In their electrifying book Let This Radicalize You, Mariame Kaba and Kelly Hayes define “a call to imagine” as “a call to arms,” in which “storytelling is a fight for the future … we write the meaning of life as we live it … it is up to us to write a story worth living”. What do we want to see in the world? What are we “for” in this wild waltz of existence? Where might our intrepid imaginations take us?

Stories are how we talk to and about ourselves. Why not make a Marvel movie featuring plants— with their miraculous, life-giving, life-saving properties— instead of human action heroes? Why not design a gladiatorial arena where two individuals can only emerge victorious once they’ve found common ground? I think of William Shakespeare’s Henry V, which contains one of the most rousing pro-war speeches ever written. In the play, King Henry lauds his small “band of brothers” fighting for England, because “the fewer men, the greater share of honour”. Might we apply this martial mentality to challenging conversations: the more difficult they are, the more glory we claim when we find pockets of interpersonal harmony? In the United States, we are entering a political sequel. We do battle inside algorithmic arenas that benefit from our polarization, our aggression, and our individualism. Now more than ever, we need supple minds, generous imaginations, and valiant hearts.

Gladiators 1 & 2 feature the character Marcus Aurelius, played by my favorite regal icon Richard Harris. But what of the real Marcus Aurelius, the Stoic philosopher? In his Meditations, Marcus Aurelius writes:

“If anyone can refute me—show me I’m making a mistake or looking at things from the wrong perspective—I’ll gladly change. It’s the truth I’m after, and the truth never harmed anyone. What harms us is to persist in self- deceit and ignorance … When you wake up in the morning, tell yourself: The people I deal with today will be meddling, ungrateful, arrogant, dishonest, jealous, and surly. They are like this because they can’t tell good from evil. But I have seen the beauty of good, and the ugliness of evil, and have recognized that the wrongdoer has a nature related to my own—not of the same blood or birth, but the same mind, and possessing a share of the divine.”

Marcus Aurelius does not worship the individual, nor does he believe in a militant commitment to Being Right. Instead, he insists upon the oneness of all things:

“You have functioned as a part of something; you will vanish into what produced you. Or be restored, rather. To the logos from which all things spring … Don’t ever forget these things: The nature of the world. My nature. How I relate to the world. What proportion of it I make up. That you are part of nature, and no one can prevent you from speaking and acting in harmony with it, always … The world as a living being—one nature, one soul. Keep that in mind. And how everything feeds into that single experience, moves with a single motion.”

So, as we seek fresh sequels and rise to meet new consequences together, let us enter the arena not armed but arm-in-arm. Let us empower the empire of the imagination, which liberates rather than conquers; for it fears nothing, but only hungers for more perspectives, more dreams, more active participants. Let us, in the words of Marcus Aurelius, allow ourselves “To pass through this brief life as nature demands. To give it up without complaint. Like an olive that ripens and falls. Praising its mother, thanking the tree it grew on.”

If you enjoy my writing, go wild and click the ❤️ or 🔄 button on this post so more people can discover it on Substack. Thank you to my wonderful friend Ben Bonnema for introducing me to the F E A S T that is Let This Radicalize You.

Watched gladiator again because of this and you are so right. We need more Maximus masculine energy in the world.